In Vermont, 13,000 people 65 and older are living with Alzheimer’s disease. By 2025, that number is expected to increase by 31%.

Caring for someone who has trouble thinking and remembering is difficult.

When family members become overwhelmed, many turn to skilled nursing facilities. But staffing shortages have severely limited the number of beds available for people with dementia and other behavioral issues, and hospitals are increasingly picking up the slack.

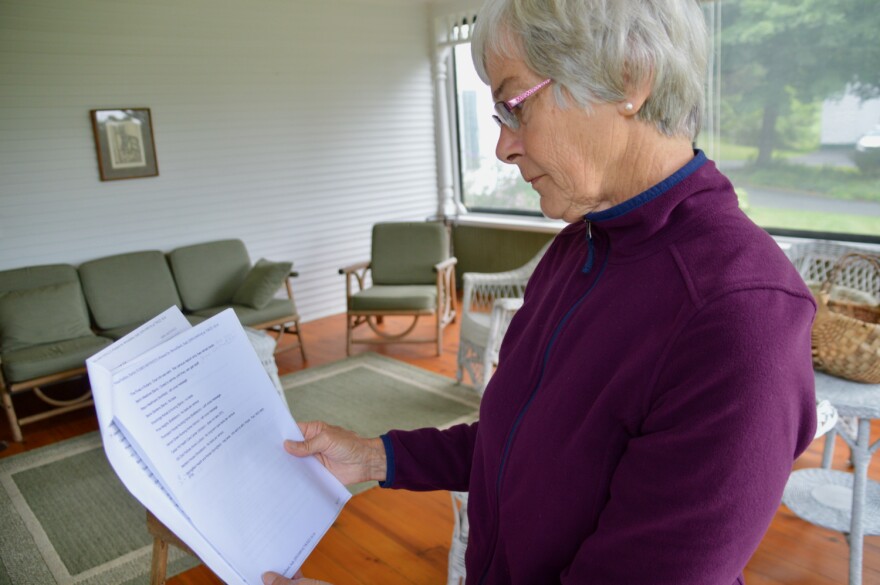

Heartbroken for a friend

Kathy Dick is a retired nurse who lives in Sudbury. Several years ago, she noticed one of her oldest friends began forgetting things.

“She was taking a couple of us out for lunch, and she couldn’t figure out how to pay the bill,” she said.

Dick’s friend had no children, was in her mid-70s and lived alone. We’re not going to name her in this story to protect her privacy.

Dick says she became increasingly worried that her friend was developing dementia.

“There were little tip-offs,” Dick said. “She’d occasionally call me and say, ‘What day is this? You know, I’m just checking.’ She couldn’t keep track of her calendar. She’d show up for appointments at 3 a.m. instead of 3 p.m., and wonder why no one was there. And I thought, something’s not right.”

Dick also knew her friend had diabetes and hypertension. What if she was forgetting or mixing up her medications? Who would know?

Nina Keck

/

Vermont Public

“And it became obvious to me that she was not functioning well, and just was deteriorating before my eyes,” Dick said.

When her friend could no longer drive, Dick set up Meals on Wheels, transportation, visiting nurses and other services. But it wasn’t enough, and the isolation of the pandemic made everything worse.

The woman’s health deteriorated, and she ended up being hospitalized at Porter Medical Center in Middlebury multiple times. Long-term care became the only option.

But finding it took months.

A crisis in Vermont long-term care

“I just could not believe it,” Dick said, shaking her head. “I just assumed that when she would need long-term care, she would be able to go to Rutland or certainly Middlebury, and barring that, maybe some place in Burlington, someplace we could drive to. But it just didn’t happen.”

Every day, the state puts out a list of available nursing home beds in Vermont, and Dick says she used it to make call after call. Some facilities might only have space for someone who needs short-term rehab, like after a hip replacement.

“One bed opened up, but it was in Bennington,” Dick said. “We didn’t want her that far away. But we made out all the paperwork anyway. But by the time we got it submitted, the bed was no longer available.”

Dick says it quickly became clear that there was a critical shortage of the kind of long-term care her friend needed. Meanwhile, her friend stayed in the hospital.

Nina Keck

/

Vermont Public

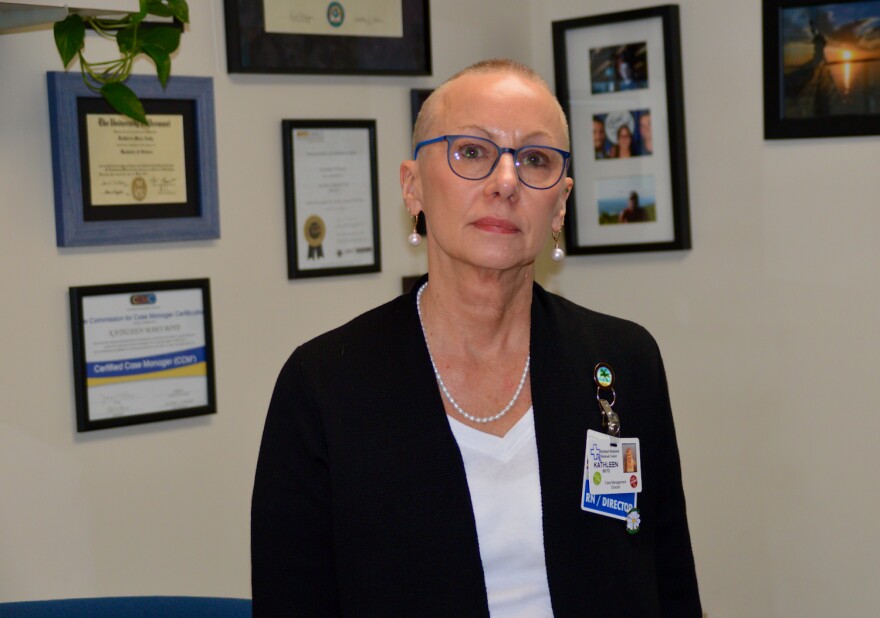

Kathleen Boyd, senior director of care management at Rutland Regional Medical Center, says this situation is not new.

“This is a growing concern, not just in Vermont but all over the country, because people are living longer,” Boyd said.

On any given day, Rutland Regional and Porter have between five and 10 so-called “custodial” patients. Not all have dementia, Boyd said. Some have serious psychiatric disorders, or are impaired because of substance misuse or a traumatic brain injury. Some have a history of homelessness or incarceration.

“They come to the emergency department for valid reasons,” Boyd said. They may have become violent or dehydrated at home. They may have stopped taking their medication or been injured in a fall.

“They need to be hospitalized,” Boyd continued. “But once they’re stable, insurance will not pay for that anymore. And we need to find a new home for them.”

But finding that new long term home is very difficult.

“Because the facilities will look at the documentation, and they will see that the patient was violent towards a loved one at home,” Boyd said. “And they’ll say, ‘We can’t take the risk, because we don’t have the staff to be able to monitor and manage this potentially agitated individual.’”

Nina Keck

/

Vermont Public

Nursing homes can say no, hospitals can’t

Because hospitals must treat the needy, many end up caring for patients like this for weeks, months and sometimes even years. With little to no reimbursement, it’s costing hospitals millions and pushing up health care prices for everyone.

“This is a problem that keeps me up at night,” admitted Claudio Fort, CEO of Rutland Regional Medical Center. “Especially when I look five to 10 years down the road as our population ages and health care costs continue to rise.”

“It’s a huge, huge issue,” agreed Dr. Stephen Leffler, president of the University of Vermont Medical Center. “Every single day, we have 50 to 70 beds taken by people who don’t need hospital care, but can’t leave the hospital.”

The situation means fewer beds are available for everyone else who may need hospital care.

“I’m an ER doctor by training,” Leffler said. “Nothing bothers me more than people, who their doctors said, ‘You need to go to the academic medical center.’ And we’ve said, ‘Yes, you do. But we can’t take you right now.’ For most of my career, that almost never happened. It happens every single day now.”

Elodie Reed

/

Vermont Public File

And it’s happening at hospitals across the country. A group of more than 30 prominent medical groups, including the American Medical Association, wrote an impassioned letter to President Biden this month calling the situation “a public health emergency.”

Staffing shortages are at the heart of this problem. Because of the pandemic-related workforce shortage, many nursing homes have had to hire traveling nurses. State officials say it’s increased staffing costs at many skilled care facilities by 150% to 250%.

In January, nearly 450 licensed nursing home beds in Vermont were taken offline because of staffing issues.

What the state is doing

State officials say they realize how challenging this issue is, and how the shortage of caregivers in nursing homes and in the community is impacting Vermont hospitals.

Megan Tierney-Ward is Deputy Commissioner of Vermont’s Department of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living. She says the state has used COVID relief money to fund short-term targeted grants for nursing homes to help with staffing costs.

The Legislature appropriated approximately $60 million to the Agency of Human Services to provide one-time workforce retention and recruitment payments to health care and direct care workers across the state.

Tierney-Ward says the state also boosted its Medicaid reimbursement rate just over 9% for skilled nursing facilities and 8% for home-based care. She said combined, those efforts have helped bring more than 200 nursing home beds back on-line.

But Tierney-Ward says to address the needs of the most complex patients, the state is negotiating with a vendor to create a new 100-bed skilled nursing unit in an existing facility. It will house long-term care patients who may be violent, those with serious psychiatric disorders, or a history of homelessness, substance misuse or incarceration.

Tierney-Ward wasn’t ready to announce where it will be located, but called it a priority.

“We’re hoping that this can start serving people in July of next year,” she said.

Stephen Leffler of UVM Medical Center says the state is working with hospitals to solve this problem and called them “a good partner.” But in his mind, the challenge is less about new infrastructure and more about the way long-term care is paid for — a system that he says is “broken.”

Because while hospitals across the state continue to lose millions of dollars providing expensive long-term care, hundreds of more affordable nursing home beds remain empty.

Correction: Nov 29, 8:25a.m. An earlier version of this story misstated the state’s plan for a new nursing home facility.

Have questions, comments or tips? Send us a message or get in touch with reporter Nina Keck: